from wwwater

阅读更多Reader

Read the latest posts from Otter Log.

from wwwater

阅读更多拼多多使用心得

from 林间空地

我发现在拼多多买的大多数东西都是有参加一些隐形(?)优惠活动的。只要原价不是个位数的东西,一般在两三天内都能便宜蛮多买下。

并不是贵才好啊。之前有次逛到一个板栗店满店 50-90 元不等的类似链接,问客服不同价格的栗子有什么差别呢,详情页好像没有体现耶。客服就跟我说都是一样的,参加了不同活动,让我挑自己看到最便宜的链接买就是……

那么怎么去刷自己想买东西的优惠价呢?我的做法是搜索想要东西的关键词,把前几项链接通通加入收藏。——收藏的操作就是告诉系统你现在想要这个多给你推这个。 反正拼多多的收藏夹等于购物车,我从来不会主动回顾,多加几项乱一点没关系。 这一步不用比价,因为有时候看起来更贵的商品链接会有力度更大的折扣。

请注意买书的话,拼多多有时候能在正版书店领到相当大的折扣(比如《卢浮宫的猫》,质量很不错的两大本漫画,控价失败到能在当当旗舰店十一元买到……),但也有时候推给你的就是盗版书店。 一般还是要看一下商家。像有“旗舰店”“品牌”标志的,当当、博库、文轩、出版社官方店……这些就是靠谱的。 而连 logo 都没有(头像显示成橙色背景上面加白底名字,有的名字甚至叫某某家居店)卖书还特别便宜的店则几乎都是盗版店,点进店铺主页资质一般可以看到是个人独资企业,保证金一般也只有一万元左右的小数字。

加入收藏后,如果这个商品有参加活动,那在拼多多近期弹出的优惠页面(可能叫“xx 地区补贴”之类的名字,有时候你刚从软件退出来就弹出来勾引你)前列就一般可以看到它。 有空的话点进去直接叉掉动画扫一眼价格就行。 点几次大概就知道想买的东西有没有参加活动,大概价格会在多少。这种弹窗经常说得花里胡哨其实显示的就是原价,扫一眼就好不用太仔细……对看过的最低价留个印象就行。

还有时候弹的页面给你说买了七八折,你要退出就挽留你说降到七五折哦。其实这些折扣名字都不用看,就是给你把同一批商品乱序刷新一下,价格一分钱都不会变的……只盯住要买东西的价格看就好啦!

要主动找这种优惠列表的话:

请看拼多多软件最下方的五个图标,点中间的那个。(它上面的字样会随日期变化,比如最近是“11.11 年度狂降价”酱紫。) 出来的页面里那个“砸我领券”的彩蛋和“三单挑战”都可以进去看看,我以前以为这所有活动页面都是不降价纯唬人的,但其实还蛮常开出来我要买的东西的,也确实便宜了。 “整点抢券”似乎不少人买好价猫罐头是从这里抢 100-50 券或者换那个六折券刷出来的。 “惊喜立减”虽然不是真的五折,但我有刷到过想买的东西在点过这个页面后降价。 “抽 100 元”页面是买完东西直接微信打款返现。虽然它名字里的“抽”、选项里的返“约”多少元感觉很可疑,不过其实下单后收到的就是写的那个数字。而且可以和后面要讲的“专属补贴”、前面说的“整点抢券”、“惊喜立减”各种券叠加,比较推荐!买之前可以把有券的页面都点一遍,不用到里面找,回来这里看标价变没变就行…… 那个“点我夺宝”几乎是没有折扣,不用浪费时间。

软件最下方图标中的第二个是“多多视频”,这个每天点进去能得一毛多钱,新用户更多,签到和提现都是点一下的事,不用花时间看,不嫌烦的朋友可以点点。 它也会给折扣,就是连划几个视频后可以看到“多多视频三单挑战”这种页面,我基本上没在它推的页面本身看到过优惠。但有时候点完再去别的页面看要的东西会发现叠上这个变更便宜了。

就总是这样,有时候虽然我没在这些活动列表里看到想要东西的低价,但是一通乱点后再回去看好的页面会发现它价格又减了……

有百亿补贴标的商品,可以先收藏然后进百亿补贴的频道去看。这个频道会有一个“专属补贴”的入口,如果在进去第一行图标划到最右看不到,那就下翻下面商品,可能有插入一行专属补贴栏目,也可能某一个商品下面有“领取 xx 元专属补贴”的小字,点进去就是了。不用划进深处,如果没看见你就退出这个频道再进去,这样也能刷到。 这个专属补贴是每一天都有更新,内容基本上就是你最近在看的商品,有时候二三十块的东西这个就降九块十块,还是蛮划算的。 不过据说在这里有写“品牌好货”(相当于拼多多背书)但不是官旗的名创优品 chiikawa 周边都是假的!需要看店名哦。

拼多多很多商品也都参了评价领现金活动,这个评价走平台的,并不要求好评,写不含标点十五字配个图就行了。不要嫌麻烦嘛,如网友所言这个可是千字百元的稿酬(?)有时候我没拍照就把东西用完了会去淘宝评价偷图,不过有次我拍我空空的掌心说吃完了包装扔了才想起来评价也是通过了……

一般它们在订单页面就会冒出小气泡让你写,不过如果在搜索框搜“评价领现金”,可以领钱的商品选项会更多。 有的东西之前显示可以评价领钱,几天后还没评价提示就消失了/金额变小了。碰到这种情况继续不评价就行,过几天又会恢复。

觉得不满意该差评如实中差评就行,拼多多商家好像没淘宝那么看重评价的,我没为此受过骚扰。(可能因为一般也不会选个人商家?)有时候还会收到三元无门槛的补偿券。 对商品有疑问跟商家沟通的话,有时候说完话窗口里就会弹出来补偿方式的选项,这是拼多多擅自提的,商家可能并不同意,甚至这时候商家还会被禁言一两分钟,挺不公平的。如果商家态度不是太过分建议还是不要点,点也选合理的补偿吧,不要逼人家。

我之前有段时间搜不到这个评价领现金页面了,当时还以为是自己黑号了,其实是因为挂梯子……关掉梯子退出来干点别的过会儿就好了。 同样的,有些商品在挂梯子的时候也是搜不出来的,买东西要比价的话请注意。

如果商家在包裹里夹带那种好评返现纸条,其实是可以举报的。虽说如此如果东西没问题+截图发过去商家有给你返钱就没必要干啥,但如果商家发这个纸条是为骗人,你给了好评店家又假装自己没办活动了,那可以找平台要这个钱。 右下角“个人中心”,页面中间有“官方客服”,点“申请处罚商家”-“钱款纠纷”-“商家承诺好评返现”即可。

在“个人中心”头像下面有个“省钱月卡”栏目,点进去一般一分钱就能办三个月。我买的有些商品会标月卡价,不知道获取的优惠跟这个月卡有没有关系。 以前这个卡会送每周一张五元无门槛的券我比较爱用,现在的券门槛都比较高优惠比较低我一般想不起来,想起来可以用用。 我以前还会看这里的“天天折扣”和“金币当钱花”栏目,但是力度完全比不上前面说的活动页面就不看了……

from sdyb

急性恋爱中毒 与正文仅有一点关系。预警:双性、约炮,不符合生理常识。 “砰、砰、砰。”张佳乐右手比作枪状,往叶修的背后往上抬三下,有强烈的意愿给叶修宣判死刑,后者在三声拟声枪响后,很遗憾地没有受到半分物理与精神伤害。 滚完三小时床单,叶修获得了婴儿般的睡眠,张佳乐获得了老爷爷般的失眠。他在深沉地思考一个问题:一对男同——即便他俩只是一对处在约炮关系的男同——但也算是一对,如果处于下位的人萎了,究竟会对这段仅靠肉体维持的关系造成多大影响?从现阶段看来,似乎还没产生任何副作用。令他苦恼的是他其实并没有丧失和叶修上床的兴趣,恰恰相反,傍晚进房间门他才摸上叶修的裤子就想先xxx再xxx然后xxx,性欲大发,精虫上脑,很符合二十出头年轻男性的精神面貌。 问题只出在今天晚上这一发,任身下流多少水,他也无法达到高潮,每次感觉快登顶身体跟中邪一样缓缓回落到中途,就这样不上不下地被吊着,要不是叶修一如往常地具备服务精神,边干穴还不忘边用大拇指高速揉搓他的阴蒂(叶修知道他喜欢被这样对待),他都要怀疑是不是叶修在刻意训练他的耐性。 意识到张佳乐不像以往那样轻易潮吹后,叶修轻轻挑眉,捞起床头柜上的矿泉水给张佳乐喂了小半瓶,又把人家在床上蹭得松垮的小辫重新绑起来,整套动作行云流水,还不耽误叶修的几把往张佳乐深处顶,连张佳乐都不得不感叹叶修在床上真是难得的勤快。 短暂休整完又专心致志做起来,叶修兴起把湿漉漉的手指往张佳乐嘴里塞,张佳乐用温热舌尖轻巧地往喉咙深处一带,津津有味地吮吸起来,叶修突然决定皮一下,双指一反往他口腔上颚刮蹭起来,张佳乐下意识干呕,回过神来气得作势要往骨节上咬,知道张佳乐不会真咬他那吃饭用的手,但他还是撤出来,在他唇上辗转着亲,边含糊地说:“还真是博美啊你。”什么bomei?脑子晕乎乎的张佳乐没反应过来,完全忘记他跟叶修说过粉丝热爱把他“博美狗塑”的那茬事。 等叶修翻烙饼一样把张佳乐转回正面,张佳乐终于发现自己今晚还没高潮过,不怪他反应慢,叶修操他讲究大开大合,光是往他敏感点上冲刺几十下就够他哼哼唧唧缓上一阵,自从开发后穴以来每次上床他的两个穴都得到足够的照顾,绝不厚此薄彼,据当事人叶某真诚声称:不同的地方有不同的滋味,前穴层层裹住几把像有百张小嘴同时吮吸,后穴紧致有弹性能完全照顾到几把的各棱各角,换着来或能形成几把永动机。扯远了,总之做爱这个活动不是非得高潮才能舒服,但就像发现自己皮肤被划破了会后知后觉地疼痛,张佳乐意识到自己没法高潮后确实开始别扭起来。 床事过半,叶修往干燥的半边床上一躺,双手按住张佳乐的腰,示意他骑乘。张佳乐半跪在他身上,后颈处的发绳早已转移到叶修手腕上,发丝被汗濡湿紧贴面颊,脸上红晕密布,只知道听从叶修的安排,他双腿张开,白得发亮的大腿根难得见光,在叶修的眼皮子底下晃来晃去。张佳乐的阴蒂已经变得红肿,自发从包皮里裸露出来,红通通的一小颗,像他老家昆明山上九月熟透的火把果。他把阴蒂朝叶修重新勃起的阴茎柱体上磨,磨的幅度太大,阴蒂吸进马眼里,两个人同时受不住地轻喘出声。 “张佳乐,晃一下。”叶修喘完,双手捏住张佳乐柔软的小腿,不让他抽出来。张佳乐依言前后轻轻晃动起来,他的阴蒂受到强烈刺激又膨大了一些,阴蒂和马眼内部互相挤压得更厉害。“好奇怪好舒服......”张佳乐眼尾泛光,逃避快感似的发散地想这个姿势日后或许会经常返场。 等阴蒂爽完张佳乐决定让阴蒂脚爽爽,他往前一挪,让阴茎滑进他体内,叶修把他的腰往下一压,他控制不住地趴在叶修身上,和叶修接起吻来,同时身体被颠起来,他含糊不清地揶揄道:“叶神腰这么好呢。”“那当然,天天坐前台锻炼腰部就为了这一刻呢。”张佳乐知道他在跑火车,笑着轻咬他嘴唇,配合动作起伏起来。阴茎持续冲撞着更靠后的位置,那里敏感点分布较少,但被叶修前所未有深入的事实让张佳乐无比兴奋起来,身体内部的快感犹如浴室玻璃上的雾气快速升腾,他难耐地扭动起来,小声道:“你翻上来好不好?”叶修起身抱住他,把他按在床上,开始加快顶撞的速度,所有敏感点终于得到全面照顾,张佳乐控制不住地呻吟起来。 这一轮叶修把张佳乐操失禁了,羞耻的感觉太强烈,于是张佳乐彻底忘记跟叶修说自己今晚还没高潮过这件事,等到他俩清理干净、转移到干净的另一张床上睡觉后,张佳乐才反应过来。 张佳乐:想哭。 虽然百思不得其解,但床上运动实在太累人,张佳乐最终屈服于困意。 “张佳乐我昨晚做了个奇怪的梦。”叶修从背后圈住张佳乐的腰,把头抵在他肩膀上,眼睛半眯着,一副没睡醒的样子。张佳乐正愁于怎么和叶修说昨晚的事情,闻言也没多想,示意叶修继续说下去。 “我梦见我们在一个奇怪的世界,大概设定是这样的......还蛮有意思,而你前次退役后百花缭乱缩回了蛋壳里,你来找我帮忙,结果是你暗恋哥,百花想帮你才这样,最后我俩在一起了,奇怪吧?” 张佳乐像中了僵直debuff一样一动不动,他诡异地联想到了昨晚的事情,不会这么凑巧吧?难不成在这个世界他也要和叶修告白才能恢复高潮能力吗?!

from sdyb

与正文仅有一点关系。预警:双性、约炮,不符合生理常识。 “砰、砰、砰。”张佳乐右手比作枪状,往叶修的背后往上抬三下,有强烈的意愿给叶修宣判死刑,后者在三声拟声枪响后,很遗憾地没有受到半分物理与精神伤害。 滚完三小时床单,叶修获得了婴儿般的睡眠,张佳乐获得了老爷爷般的失眠。他在深沉地思考一个问题:一对男同——即便他俩只是一对处在约炮关系的男同——但也算是一对,如果处于下位的人萎了,究竟会对这段仅靠肉体维持的关系造成多大影响?从现阶段看来,似乎还没产生任何副作用。令他苦恼的是他其实并没有丧失和叶修上床的兴趣,恰恰相反,傍晚进房间门他才摸上叶修的裤子就想先xxx再xxx然后xxx,性欲大发,精虫上脑,很符合二十出头年轻男性的精神面貌。 问题只出在今天晚上这一发,任身下流多少水,他也无法达到高潮,每次感觉快登顶身体跟中邪一样缓缓回落到中途,就这样不上不下地被吊着,要不是叶修一如往常地具备服务精神,边干穴还不忘边用大拇指高速揉搓他的阴蒂(叶修知道他喜欢被这样对待),他都要怀疑是不是叶修在刻意训练他的耐性。 意识到张佳乐不像以往那样轻易潮吹后,叶修轻轻挑眉,捞起床头柜上的矿泉水给张佳乐喂了小半瓶,又把人家在床上蹭得松垮的小辫重新绑起来,整套动作行云流水,还不耽误叶修的几把往张佳乐深处顶,连张佳乐都不得不感叹叶修在床上真是难得的勤快。 短暂休整完又专心致志做起来,叶修兴起把湿漉漉的手指往张佳乐嘴里塞,张佳乐用温热舌尖轻巧地往喉咙深处一带,津津有味地吮吸起来,叶修突然决定皮一下,双指一反往他口腔上颚刮蹭起来,张佳乐下意识干呕,回过神来气得作势要往骨节上咬,知道张佳乐不会真咬他那吃饭用的手,但他还是撤出来,在他唇上辗转着亲,边含糊地说:“还真是博美啊你。”什么bomei?脑子晕乎乎的张佳乐没反应过来,完全忘记他跟叶修说过粉丝热爱把他“博美狗塑”的那茬事。 等叶修翻烙饼一样把张佳乐转回正面,张佳乐终于发现自己今晚还没高潮过,不怪他反应慢,叶修操他讲究大开大合,光是往他敏感点上冲刺几十下就够他哼哼唧唧缓上一阵,自从开发后穴以来每次上床他的两个穴都得到足够的照顾,绝不厚此薄彼,据当事人叶某真诚声称:不同的地方有不同的滋味,前穴层层裹住几把像有百张小嘴同时吮吸,后穴紧致有弹性能完全照顾到几把的各棱各角,换着来或能形成几把永动机。扯远了,总之做爱这个活动不是非得高潮才能舒服,但就像发现自己皮肤被划破了会后知后觉地疼痛,张佳乐意识到自己没法高潮后确实开始别扭起来。 床事过半,叶修往干燥的半边床上一躺,双手按住张佳乐的腰,示意他骑乘。张佳乐半跪在他身上,后颈处的发绳早已转移到叶修手腕上,发丝被汗濡湿紧贴面颊,脸上红晕密布,只知道听从叶修的安排,他双腿张开,白得发亮的大腿根难得见光,在叶修的眼皮子底下晃来晃去。张佳乐的阴蒂已经变得红肿,自发从包皮里裸露出来,红通通的一小颗,像他老家昆明山上九月熟透的火把果。他把阴蒂朝叶修重新勃起的阴茎柱体上磨,磨的幅度太大,阴蒂吸进马眼里,两个人同时受不住地轻喘出声。 “张佳乐,晃一下。”叶修喘完,双手捏住张佳乐柔软的小腿,不让他抽出来。张佳乐依言前后轻轻晃动起来,他的阴蒂受到强烈刺激又膨大了一些,阴蒂和马眼内部互相挤压得更厉害。“好奇怪好舒服......”张佳乐眼尾泛光,逃避快感似的发散地想这个姿势日后或许会经常返场。 等阴蒂爽完张佳乐决定让阴蒂脚爽爽,他往前一挪,让阴茎滑进他体内,叶修把他的腰往下一压,他控制不住地趴在叶修身上,和叶修接起吻来,同时身体被颠起来,他含糊不清地揶揄道:“叶神腰这么好呢。”“那当然,天天坐前台锻炼腰部就为了这一刻呢。”张佳乐知道他在跑火车,笑着轻咬他嘴唇,配合动作起伏起来。阴茎持续冲撞着更靠后的位置,那里敏感点分布较少,但被叶修前所未有深入的事实让张佳乐无比兴奋起来,身体内部的快感犹如浴室玻璃上的雾气快速升腾,他难耐地扭动起来,小声道:“你翻上来好不好?”叶修起身抱住他,把他按在床上,开始加快顶撞的速度,所有敏感点终于得到全面照顾,张佳乐控制不住地呻吟起来。 这一轮叶修把张佳乐操失禁了,羞耻的感觉太强烈,于是张佳乐彻底忘记跟叶修说自己今晚还没高潮过这件事,等到他俩清理干净、转移到干净的另一张床上睡觉后,张佳乐才反应过来。 张佳乐:想哭。 虽然百思不得其解,但床上运动实在太累人,张佳乐最终屈服于困意。 “张佳乐我昨晚做了个奇怪的梦。”叶修从背后圈住张佳乐的腰,把头抵在他肩膀上,眼睛半眯着,一副没睡醒的样子。张佳乐正愁于怎么和叶修说昨晚的事情,闻言也没多想,示意叶修继续说下去。 “我梦见我们在一个奇怪的世界,大概设定是这样的......还蛮有意思,而你前次退役后百花缭乱缩回了蛋壳里,你来找我帮忙,结果是你暗恋哥,百花想帮你才这样,最后我俩在一起了,奇怪吧?” 张佳乐像中了僵直debuff一样一动不动,他诡异地联想到了昨晚的事情,不会这么凑巧吧?难不成在这个世界他也要和叶修告白才能恢复高潮能力吗?!

from nolookpass

小七的学生的故事。

很多年以前,有一对姐妹,妹妹是智力障碍,被家里人卖给外地的和尚,生下一个男孩,和尚把女人的牙齿全部敲掉,让她在路边乞讨,恰好在街头碰到南通本地的商人,商人把女人和男孩带回老家,后来男孩学歹偷盗,不知所踪。女人很想要小孩,于是买来一个漂亮的小女孩,和姐姐一起抚养,这个女孩就是小七的学生小蔡,她说,我一出生就有两个妈妈。

小蔡小学的时候成绩不错,后来有一次被老师调到后排,回家告诉妈妈们,妈妈们就去告诉老师,不要欺负我们家孩子,老师转头告诉班里的孩子,你们不要跟小蔡玩,她会告黑状。于是小蔡被分到差生区,从那之后屁股没有沾过座椅,一到学校就罚抄好几遍的语文课文,到中午,南通当地还要上课,他们几个差生就被老师罚到教室改的食堂打扫卫生。因为限制用餐时间,很多学生会把残羹剩饭倒在桌肚里,小蔡说她的中午就在清理食余垃圾和老鼠尸体碎片中度过。还有一件事,小蔡的妈妈们虽然贫穷但给了她很充足的关爱,有天给她包了漂亮的书皮,这本书后来被老师借走,又被小蔡在食堂的桌肚里发现碎片。当时和她玩的同学很少,其中一个是广西来的女生,成绩很好,排在班里前几,一毕业就被家里人安排相亲嫁人了。另一个是一个小胖子,后来去了别的中学再没有联系,不过某次在路上碰到,还邀请小蔡去他们家玩,小蔡对此印象深刻。 上初中之后有所好转,小蔡的语文成绩很不错,她调侃可能是实在抄了太多遍的书获得了语感,但是数学英语一塌糊涂,初二开始成绩也不行了,到初三,老师为了升学率劝她不要中考,家里人还是坚持让她完成毕业考,老师就又阴阳怪气地鼓动同学孤立小蔡,终于在中考前一个月,小蔡退学。当时有一个初中同学已经在缝纫厂之类的干了一年,小蔡就加入了她,在后来的十几年里,她做过很多工作,餐饮,收银,护肤前台,茶艺服务,因为家境贫寒却面容姣好,她在后来的时间里又受到了很多欺凌。她自学翻墙,了解女权主义,了解心理学,想要学习一门外语(于是找到小七),想和更多的人沟通,想让她打工遇见的妹妹们不要那么累。工作这么久她一直没有积蓄(好不容易攒了点,家里人生病又都花光),不过她一直很乐观。小七说一开始完全感觉不到她是初中都没毕业的人,说话条理清晰,表达能力极强,还会像北京人一样说“您”那样客气。相比一些同学,家庭幸福一路考学至硕博思想却还是传统逼仄,在这个世界把所有刻板印象里关于觉醒觉知的路都堵死的时候,小蔡还是自己找到了一条走向通识教育、走向更开阔世界的路。不止是女权主义者这一点,而是水泥缝里长出一棵野草,这种坚韧让我非常震撼感动。

这个女生的事情深深鼓舞了我,无端让我想起《孤高之人》里的森文太郎,我要做的只是独自攀山,其他的一切,都是杂质而已,我要做的事情,不需要任何人知道。

from nolookpass

住在太子附近,走去深水埗的路上一路都是非常破旧的老楼,印刷着掉漆斑驳的红字,发润行,之类,随手拍一张照片,像是自带胶片褪色的质感一样来自上个世纪。上个世纪,1990s,外公外婆都还在世的时候,回到龙海,姨妈一家就住在相同质感的房子里,于是我站在香港街头,想起小小的我在老楼的楼梯间环形而上,似乎某些夏天还住过好长一阵,这样的记忆已不真切了。我正站在香港的街头,唤醒的是在老家童年的记忆,这让我感到有些新鲜。当时的姐姐说她喜欢狗,不喜欢猫,猫的眼睛让她害怕。很多年后,姐姐离婚后来又险些入狱,她对我说她喜欢猫,不喜欢狗。我不想质疑我的记忆,尽管我知道某些时候大脑会欺骗我。龙海的特产甜品是双润糕,或者双糕润?我总是记不清到底是哪一个,一想起这个词耳边是模糊的闽南语,这是一种黏糊糊的甜食,能把老人家的假牙黏下来,但老人家还是爱吃。在香港一路Google map导航,我想起我总记不起去外婆家的路,全程都靠妈妈带着,这里拐,闻到猪圈传来的泔水味再过几个转角就到。这真的是我的老家吗?在很多年后的异乡,我对这些记忆产生的怀念,或许只是满足了此刻的我的一些投射而已吧。我对海澄并不熟悉,儿时被带着回去探望外公外婆,也总是疏离而不自在的(我非常清楚这和家人们是否爱我无关,只是很少呆在他们身边,所以并不相熟)。在2008年外公去世以前,海澄老家的巷子对我来说是每年走一遍、每年都忘记怎么走的存在,到达目的地我就开始想要离开。而在十七年后我真的离开了,我走在深水埗的街上,我开始怀念当年那个想要离开的时间里的我,唯一的烦恼是外婆家没有好玩的,没有什么同龄的朋友,我自然坐不住。我其实一直坐不住,于是我走到北京,走到香港。直到出走之后,我才渐渐明白家乡对我的意义,在拍下这张就像是来自上世纪的胶片相片之后,心头不可避免地生起一丝对过去的怀念,过去不好不坏,但我已结结实实地走在路上了,而心中一闪而过来自老家的模糊景色可以让我想念,这让我觉得庆幸又安全。 写得很乱,很久不写东西就有一种用非惯用手刷牙的感觉。挺好的,我要继续写下去,是垃圾也不要紧了。

办一张流量卡

from 林间空地

事由

八月底校园卡合约期将要结束,听说之后会变成高价低流量的套餐,我的常在地也绝不会再是学校那边,所以我决定把目前的这个校园卡套餐改成最低价的保号套餐,然后另外用一张流量卡。

改保号套餐的过程比较顺利:我的卡是联通的,拨打 10010,对 AI 说要转人工,它让按键操作,按 0 选择继续等待人工客服,对客服说我要改成八元套餐,客服一番操作就好了。变更会在次月月初生效,有 200M 流量和 30 分钟通话。

但流量卡的购买过程还比较波折,我没想到自己在变更前预留的半个星期是不够的。

可能的陷阱

首先是网上搜了些经验,知道流量卡基本上只能在网上、非官方渠道办理,而这些渠道又存在很多套路。 比如说:

- 可能发的不是正规电话卡而是“物联卡”,什么意思,不懂,总之卡面上没有 20 位 ID、运营商处根本查无此卡;

- 可能告诉你资费是 19 元上百 G 流量,其实几个月后就抬高价格,流量也缩水;

- 可能说 19 元月费,存 100 返 120 每月到账 10 元,其实这 10 元是要每月自己找商家去领的,而且这 10 元加上你额外付的 19 元才是真实的月费(29 元);

- 可能店家商品详情有隐藏小字,说如果你的卡未审核通过就会“为你自动匹配最优其它选项”,也就是说,商家可能不经通知就给你换一张和你所选运营商、套餐完全不同的卡;

- 可能你的信息会被泄露,在自己选中的那张卡到手前就会有人送给你别的卡还催你当面激活,人走了你才发现情况不对……

即使是像“支付宝号卡中心”小程序这样看起来比较“正规”的地方,背后也是一个个第三方流量卡代理,仍然有这样潜藏的、不省事的陷阱。 更不要说淘宝直接搜到的流量卡商家……客服说话就给人不可信的感觉,翻一翻评论区几乎找不到一个真人评价,问答区也常有提醒大家别上当的。

其实,这些代理商未必真的比我们对运营商的种种规则了解更多,它们的目的只有把卡片推销出去赚取佣金。像有一些卡片其实有非常明确的年龄限制(18-25岁,部分地区放宽到28岁)或地区限制,但这些商家不会在一开始就告诉你,只把最诱人的套餐贴出来,之后看你的身份信息不合就随便给你申个别的高佣金卡片就是了…… 所以,我考虑了自己去当一个流量卡代理——据我的搜索结果这渠道就像做淘宝返利一样好找,有现成的平台可以几分钟自助注册成功,平台上对套餐的说明内容是纯文字的,很清晰透明,自己给自己挑合适的套餐就好了。

主流申卡平台

流量卡代理有两个主流平台:172 号卡,号易。

开始我是想用号易的,因为据说 172 号卡各事务处理进度更慢,佣金提现还要签订电子合同。虽然合同据说也没什么问题,只是用来限制你不要虚假注卡骗取佣金又注销,但我还是倾向于约束更少的平台。 不过我连号易的官方网站都找不到。 App store 搜出来两个结果,评分更高的“号易”直接是个个人开发者名字,评分低一点的“号易号卡”我记得下载后注册时会提醒软件版本低要我更换。公众号搜索能有一堆挂着“官方”名字头像、归属公司各不一样的账号,其中颇多会推给你“官方推荐码”——假的,这些都是一些个人代理,你注册时填写它们的推荐码就成为了它们的“下线”,会被它们抽取佣金。虽然我们自用卡片不是那么看重佣金,但给骗子送钱总是很不爽的。再找官方网站……这个我都找不到!常被提及的网址都长着奇奇怪怪域名,进去注册时上面会飘动“官方推荐码”的——也是骗子。

搜了这么多我已经很不耐烦了……网上有特别多复制粘贴来的大同小异骗子信息,一个个都叫你千万不要被骗,最后图穷匕见需认准官方推荐码 xxxxx……翻起来真的非常浪费生命。 所以其实最后我用的是 172 号卡,至少它在 app store 只有一个唯一 app……嗯……我也不知道是不是官方……

找个中介

不过,在转向这“最后一步”前,甄别信息已经看“麻了”的我想的是还是把这份佣金交给别人去赚。 刚好这时候我刷到了一个起码是在自己用人话写文的卡代,看他评论区也没有催促别人选择自己,是比较耐心地在解答路人问题、帮忙鉴别信息真伪,蛮真诚的样子,我就先联系了他。

这个人,怎么说呢?他确实是踏踏实实在做卡代的。但就像我前面说过的,成为卡代的渠道非常简单,卡代可能并不了解比我们更多的信息或有更多的权限。办理过程中你要查询什么或遇到什么问题,找他,也只是等待他有空去查询或找客服再转述给你,徒然增加了等待时间。个人卡代不能给你提供任何便利。 只要你不晕字,那么自己看号卡平台的说明已经足够清晰透明了,基本上不需要一个中介再给你翻译一遍。

加上微信后他给我推荐了一张电信卡,标题的 19 元 80G 指的是 50G 通用流量+ 30G 定向流量,说在七十天后会有电信客服打来电话,接完电话才算完整地激活这个卡片套餐的内容,每月的通用流量会随机变成 80G 或 150G。 我觉得七十天太长,定向流量用不上,在学校习惯阔绰地用流量,不知道 50G 够不够,问他有没有其它选择。

他又推来一张联通卡,29元 180G 流量 30 分钟通话,激活时需要充 100 元,这 100 元销号时也不能退,算是一个防人早早注销的保障。 我表示满意,但申请这张卡需要上传身份证正反面照片以及一张背景不杂乱的上半身照片,我还是有点疑虑,想要打上水印。 他说这些信息是直接发给运营商的,他本人并不能查看,没事的,但如果我还是害怕,那就打上水印去上传好了,应该会审核失败,但这个失败结果可以在中国联通的官方 app 上“我的订单”-“购物订单”页面查到。届时我在联通 app 上重新上传无水印版照片就好,那样应该可以放心。 我说好的,在各图片上都打了“仅供25年8月申请联通电话卡使用”的水印,但过了两三天都没办法在“购物订单”看到这张卡,问他他也只能叫我等待。最后他那边订单查询说[用户身份证号输入错误],大概是照片审核不过的意思,说现在联通 app 里应该可以查到那个订单,我表示仍然查询不到。 这时候我要出远门,不方便接收这张需要快递员当面激活的卡片,说等我回家再重新申请。回家之后套餐已经下架,告诉他后他又给我推荐另一张电信卡。虽然我在新卡片申请页面的左下角发现可以查询订单,查到的这个旧订单详情好像可以重传身份信息,但我想到不顺着人说话要跟人多沟通就犯怵(……),还是申了新卡片。

这张卡又是电信的,说每月 29 元,首月免费 50G 通用流量+ 30G 定向,三十天内接电话后每月多加 105G 通用流量。 他让我看看发货地区发我们这儿吗,我当时没注意到,把信息填完了反正没报错,他说那应该就是能发。这样过了几天我问他能帮我查查发货没吗,他说稍后发我就没了动静,次日我自己从页面左下角查到是审核失败。问他这可能是因为什么呢,他去找客服,说是因为我的地址在不发货地区。

于是再换……下一张卡是移动的,28 元每月,150G 通用流量和 300 分钟通话,送一些我用不着的平台会员。申请需要三照。我上传后平台报错说我超过年龄,原来这张卡有 18-25 的年龄限制。 我问他还有别的卡吗,他说暂时没有合适的,如果我不要第一张七十天 50G 流量的就只能等等,我说好的。然后自己下载了 172 号卡……

172 号卡

邀请码

注册时要填邀请码嘛,前面说过很多人邀请码发出来就是为了赚你的佣金抽成,但从我申请第一张卡到这一步已经经过了半个月,我已经,不在乎了。搜一个不发太明显诈骗信息的女号发的五位数短码就用来注册了。

为什么要五位数的短码呢?因为我感觉,越多位的数字可能代表这是一个等级越低/注册时间更晚的用户,伊自己不被抽成都说不定呢还怎么少抽我的成。

不过注册完我发现这个推荐码是这么搞的哈哈:长度数字自选,不跟别人撞上就行,位数和“更规律的数字”都不能说明任何。

据说填错推荐码可以注销。又据说注销后需要等待 72 小时才能重新注册。我没有再做尝试。

据说填错推荐码可以注销。又据说注销后需要等待 72 小时才能重新注册。我没有再做尝试。

运营商和套餐选择

进入平台的商品页面是有四个运营商分类:电信、移动、联通、广电。 这个广电我是开始弄流量卡才第一次听说,虽然号称国内第四大运营商,并不是一个杂牌公司,但它在各地铺设的信号基站数量肯定是远小于前三家的,所以虽然价格更为实惠,但基本上不用考虑。 我最后办的这个电信卡还老是从 5G 跳到 4G 呢,以前用的联通卡也经常信号弱弱的,不能接受信号更差了……

前三家的 app 里搜“附近 5G 覆盖”能查出一个信号覆盖小地图,据说可以通过对比这个验证出哪家运营商在你家附近信号铺设得最好。 不过我没查……我凭经验也知道我们这边移动信号最好,但另两家再差也不至于用不了嘛。

在平台上看移动的卡,要求似乎是最严格的。除去不发我家这边的套餐,每一张卡都要求年龄 18-25。除非我立刻去外省旅游,不然就没办法申啦。 联通倒是有年龄限制更宽松、全国可申的套餐,可惜我点进详情也发现本省的链接已堂堂下架……可能之前卡代发给我的就是这款吧! 那么就只能选择电信。 (PS:我当时是这么选了,但后来发现每天平台上都会上架下架一些套餐,愿意多等两天的话选择会多一些。)

我挑了一张 19 每月 60G 通用流量 + 50G 定向流量 + 200 分钟通话的卡,这张要求在申请结果出来前就预充 100,不需要在号卡平台上传三照,是自主激活,最后在电信公众号做的身份验证。定向流量可以用的软件包括 bilibili 和网易云音乐(为什么我从卡代分享给我的详情页面都看不到定向流量具体可以用在哪里,明明他应该是直接把平台生成的链接推给了我,神秘……)。 为什么我咨询的卡代没有给我介绍这张呢? 善意地想呢是 60G 流量看起来没有几十天后变上百的诱人,可能我说 50G 不够用他就觉得 60G 也不会够用。 更可能的原因是,这张佣金只有 65 元,比起别的卡上百元的佣金有些微薄了……这也是我想推荐大家自己成为卡代的理由!别人不会给你看全所有选择。

办理过程

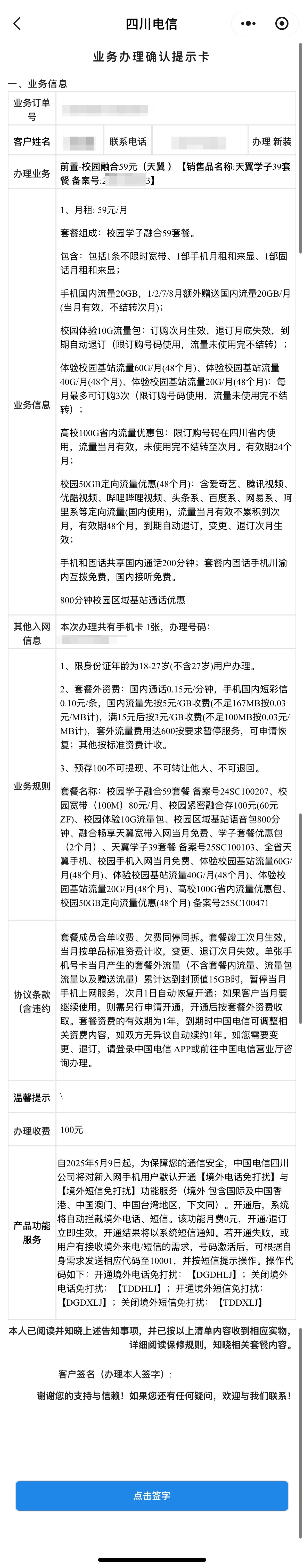

自选的这张卡办得比较顺利,11号中午下单,13号有四川电信的客服打来电话,问完我名字后给我发一条短信要我告知验证码。 短信内容是这样:

【四川电信】尊敬的用户,您本次短信验证码为******,用于“前置-校园融合59元(天翼 )”业务办理的联系号码确认,有效期5分钟,请及时使用。

15号下午我接到邮政电话说快递到了,去菜鸟驿站取的时候还碰到他跟驿站老板有点争执……似乎因为老板认为这个电话卡信封是一个空包,不愿意接收💦…… 总之,就这样像收一个普通快递一样收到了。 没有碰到要我激活别的卡的骗子也没有碰到需要顶着快递员视线检查包裹的社交压力情况……

如果选择的卡详情写了要快递员激活,那么请在收快递时一定先检查好订单详情里的物流号/手机号和包裹是不是对得上!对不上就拒收吧。

流量卡的套餐构成

至于为什么短信写的是 59 元融合套餐呢? 容我带大家看一下套餐办理页面进行一个解读! 它是这么写的:

原套餐59元,包含20G通用流量+200分钟通话,1/2/7/8月额外赠送20G。套外流量5元/G,通话0.15元/分钟,短信0.1/条 优惠详情 下单预存100元 享受优惠 优惠后:19元60G通用流量(寒暑假80G)+50G定向流量+200分钟通话,优惠期2年,到期可续。 优惠说明 1.叠加40元减免包,有效期2年,到期可续 2.叠加40G通用流量+50G定向流量,有效期2年,到期可续 综上: 首月19元全扣,套餐内容按天折算到账,次月起每月19元包60G全国通用(寒暑假80G)+50G全国定向+200分钟通话,到期可续

首先看第一行,它表示我的电话卡带的基本套餐就是 59 块钱,而且里面平常只有 20G 通用流量和 200 分钟通话,碰到寒暑假才会多出 20G。我在进入电信公众号激活卡片的时候,能看到的只有这个基本套餐的合约。

要达到它承诺的 19 元价格呢,如优惠说明后第一点所言,在我激活卡片后,它会给我叠一个每月 40 块的返现包,通过 59-40=19 这样子抵消实现。 要达到承诺的 60G 通用流量,也是同理,照优惠说明第二条,给我再叠一个流量包那样子实现。(不过实际上是基本套餐 20+10,激活后流量包 30 酱紫,不重要)。

这就是前面卡代给我推的那些套餐要等三十天七十天的原因,它们的叠加包不是即时到账的,可能需要再收一个验证码。

而这些卡片之所以会有年龄限制和寒暑假多给通用流量的安排,则是因为,它们…其实是校园卡来的! 可能学校营业厅的人跟号卡平台合作了吧……我拿到的卡板上还写着最晚激活时间是 22 年 11 月呢💦……

下面是我在激活卡片后一小时陆续从 10001 收到的短信大概内容:

【生效提醒】您于2025-09-15 17:35:07在省电渠_人工受理渠道办理的校园区域基站语音包800分钟(方案编号:xxxxxxx)已成功,新资费将于2025年09月15日 17:37:24生效,用户未变更则资费长期有效。资费说明—赠送800分钟校园区域基站通话优惠,具体业务说明详见业务登记单。如您需要变更、退订,请登录中国电信 APP或前往中国电信营业厅咨询办理

【生效提醒】您于2025-09-15 17:34:04在省电渠_人工受理渠道办理的校园入学标识已成功,新资费将于2025年09月15日 17:37:24生效,到期时间为2030-09-01 00:00:00。

【生效提醒】温馨提示:您于2025年09月15日 17:33:40在省电渠_人工受理渠道办理的校园学子融合59套餐(方案编号: xxxxxxx)已成功,套餐资费于2025-10-01 00:00:00生效,用户未变更则资费长期有效,资费说明—套餐费59元/月,包括1条不限时宽带、1部手机月租和来显、1部固话月租和来显;手机和固话共享国内通话200分钟;手机国内流量20GB,1/2/7/8月额外赠送国内流量20GB/月(当月有效,不结转次月);套餐成员本地群内通话优惠,国内接听免费,具体业务说明详见业务登记单。如您需要变更、退订,请登录中国电信 APP或前往中国电信营业厅咨询办理,新加号码资费将在办理次月生效。 新人福利,送您10GB国内通用流量,请点击 http://a.189.cn/RBzbeM 下载中国电信APP领取。满意服务,10分信赖!

【生效提醒】您于2025-09-15 18:03:46在 xxxx 大学校园厅-xxx 办理的校园学子融合赠送40元/月(方案编号:xxxxxx)已成功,新资费将于2025年10月01日 00:00:00生效,到期时间为2029-10-01 00:00:00。资费说明—分48个月,每月赠送40元(限当月使用),只可抵扣同一账户下产生的校园融合套餐费,具体业务说明详见业务登记单。如您需要变更、退订,请登录中国电信 APP或前往中国电信营业厅咨询办理。

【生效提醒】您于2025-09-15 18:03:40在 xxxx 大学校园厅-xxx 办理的高校国内流量包30GB(方案编号:xxxxxx)已成功,新资费将于2025年09月15日 18:04:23生效,到期时间为2027-09-01 00:00:00。资费说明—每月免费赠送国内流量30GB(当月有效,不结转),具体业务说明详见业务登记单。如您需要变更、退订,请登录中国电信 APP或前往中国电信营业厅咨询办理。

我在中国电信 app 可以查到的流量构成也没有问题,至此就算安全下车啦。(主套餐只有 9G 流量而非 20G,是因为首月的资费和流量都是按自然月的剩余天数折算的):

隐私相关

不过我还要提一下隐私问题。前面我表示上传照片的疑虑时,卡代不是告诉我他看不到这些信息吗? 身份证图和免冠照他的确是看不到的,不过从 172 的订单页面,客户的姓名、手机号、地址都是完全暴露在卡代面前的。 还能申请解密身份证后六位呢,我点了一下看是说有两次这个权限……

别的

我这卡都激活一天了,在 172 号卡这个订单详情还是“未激活”状态。之前接完运营商电话,这边订单备注也没有“已提运营商”(指已经把信息交由运营商审核),状态是等我收到货才更新的。我在小红书看到偶尔有人的卡都用上一个周一个月了,订单这里也还没有跟进的。 如果急着要那笔佣金的话,这种情况似乎是要找客服,没效果就进一步打工信部电话 12300 投诉。172 号卡提现前需要签合同,不想提现不签就行,想提的话签完拿到钱后也可以找客服解约。解约时可能要填“上级”(你写的邀请码来源)名字和邮箱,不知道问客服就行。 对于像我这样只是想办卡自用,不那么在乎佣金的情况,我提起这点是想再说一遍信息延迟很严重,再加一个中间人帮自己查更是又慢又没用,真的是自己去号卡平台申请比较直接省事啦(:3」∠)

更新:我的 56.4 元佣金已经提现到账啦!这么一算月费又减了不少。九月中激活的卡,是隔月(十一月)月初显示的已激活可提现。原本是六十元佣金但扣了一些手续费酱紫。

from blueplaid

#

回首这半年,自己好像寻寻觅觅忙忙碌碌,最后竹篮打水一场空。

再把目光回放地更远一些,这么多年,我都一事无成,用世俗的标准来说是这样,用更多元的标准来说……那样的标准我暂且还没建立起来。

二十有三年内,我浑浑噩噩地生长,所幸保有一块无人叨扰的自留地。二十三年后,我被断断续续的瘟疫、封锁、政治性抑郁所击垮。我的一切计划,我原本信服的人生轨迹,都发生了天崩地裂的变化。

这种变化,对于我这样的人来说,起码一开始,算不得一件好事,至于去路如何,看我未来转机了。我考学过很多次。用我爹的话来说,我太好高骛远,选的学校其所需分数远超自己所能。我同意。但我其实也没办法,我听取过建议,换一个相对来说更有把握的学校。可随后备考的每一天我都兴致缺缺。当时我不知道,我自己是兴趣导向的。

兴趣导向?那是一种动机类型,也就是说,我做事,只能受强烈的兴趣驱动,或是意义驱动、结果驱动。当一件事可以即时地给我最大的好处,我才能去执行并完成它。否则,我连完成都做不到。

其实这几年,也有一年中,我真切地意识到这一点,然后尽己所能,激励自己,为我做的所有事情赋义。副作用是,那些意义经受残酷现实摧压的时候,简直像泡沫一样在霎时间破灭。

嘶——我当时怎么没想到,问题并不出在我为事情赋义这个举动本身,问题在于我当时赋义的内容太过理想化了啊。

总之,在我最激烈的一波政治性抑郁后,我意识到自己没办法再接受考学了,我不想再碰一点政宣相关的内容。那留学吗?我考虑过,查阅资料、咨询熟人、回母校取成绩单……最后不了了之。虽然我还是去考了雅思。也许是想着不考白不考吧。考出来对工作也有助益。总而言之,我放弃留学,一来是我对外语会有经常性的排斥周期。比如我考完雅思后,就再没开口练过口语,不愿再高频地碰英语材料,甚至美剧英剧也看得少了。不排除其中有这一原因:我备考阶段逼迫自己过度高频地暴露于英语语料中,于是这半年我在经历一段语言学习的反叛期?我最近又开始渴望说英语,这足以验证这一点。二来,我本身是语言专业,我却没有修过第二专业,这使我在可申请院校及专业上都有太大的限制。三来,我后来罹患的焦虑症,使我难以继续承受申请的压力,我又不愿意放手全权托付给中介,我不放心,我不想迷迷糊糊地就去读了一个莫名其妙的专业,又马上回来。

以上又应证了我是兴趣、意义、结果导向的。我还十分在意我做的事情由我的思路掌握这一点,至少事情得由它探明、明晰。因为我得对自己负责,否则我该怎么面对可能有的一切烂摊子呢? 如果我希望留学,或是终极地润,起码我应该对目的地和在那边能做的事,有所向往。这又引出了我人生中另一大谜题,我究竟想做什么?我究竟能做什么?我想我再出来找工,为的就是探明这一点。果然这段经历更确切地帮我排除了一项——我是绝对不适合,也不想在教育行业投入精力和时间的。

我这人真的不爱管理人。当我被要求像训猴一样,操练那些小孩时,我深感为难。我明白那些口令对于孩子来说,也不过是一种游戏。但这份职业每天的执行人,是我自己。我受不了每天要调动如此之多的心理精力,顶着那份为难,去表演、去操练小孩、让他们竞争,然后自己也陷入恶性竞争……这就是在说那个公司那个部门诡异的人际环境了……我此刻不想赘述。

from nolookpass

我上一次坐在电脑前面打下完全不功利的文字是什么时候? 我喜欢窗外暴雨的声音,一个人在漆黑的房间里,不知道多远外有闪电与雷鸣,仿佛整个世界的人都跟我一样窝在漆黑的房间里,于是所有人都孤立,所有人都孤独,这种感觉总让我很安心。 因为太久没写过东西了,所以现在全无语感,说话颠三倒四乱七八糟,无所谓了。先这样写着再说。

我对自己身体的关注度太低了,总是在磕磕碰碰的淤青和伤口出现后才察觉到自己受伤了,而且完全想不起来到底是在哪里磕碰到。或许我不该把这个现象本身当成我人生的隐喻了?

在很多别的地方,在我赛博自杀的所有平台里,我都不再谈论“我”了。抑郁的时间里我“我我我我我”,抑郁的时间后我把这些“我”都杀死了。或许我不该害怕这些“我”?

中午做梦梦到我是一个学广告的孤儿院出身的女生,本来和班上有点内向的喜欢电影的男生不合,但homestay的家庭刚好在一起,那个老房子的四面墙都漏水,到处都是老鼠,房子里的猫(不知道是不是家养的)都习惯了水房子,躺在水洼里,也不抓老鼠,我吓得紧紧抱住男主。后来我的创意被一个富商的老婆看上(大概是把产品做成一个可以登上去的很大的圆台,圆台的色号和产品一致,上面还有一些精巧的玩法,所有的圆台从高空俯瞰是一个更大的图形之类。。。),本来靠这笔钱我和男生可以搬出水房子,可是一个酒庄的奸商诬陷我抄袭,我在学校很崩溃,男生把我拉走,没说什么话,只是抱着我,我听到旁边的同学说,他们不是不对付吗,怎么现在关系这么好?视角一切,男生和老家的朋友讲电话,说生活或许会好起来之类,走在静谧的石子路上,而我,或者说女主吧,去买五颜六色的卡通打糕,就是一盘五颜六色的东西被打成糕状,周围都是小朋友在排队,看到我哭了都安慰我,说吃点打糕就好了,我在梦里(此时确实是第一人称)想着小孩真的很好很善良,没有被任何坏东西污染过,然后想起童年很孤独时候和玩伴互相支持的感觉,想着现在在陌生的城市遭人诋毁,也不是受不了了,只是觉得孤独,于是就一边吃打糕一边痛哭一场。 我的梦似乎没有什么触觉?但和人紧紧相拥能获得一些短暂的安全感。醒了之后我想男主和女主其实都是我,一个阴湿我一个阳光我,从不能理解彼此到接受彼此,虽然梦的最后我是哭醒的,但并不觉得悲伤。是一个孤独但是充满力量的梦。

张新杰的公馆记录.1

from REKISHI

张新杰有一本小册子,放在女仆长裙的隐藏口袋里时不时拿出来写上两笔,方锐说他是阎王笔,“上次被罚戴老鼠口水巾连肖时钦都笑了求求你不要记我的名字了!”张新杰没理他还是参了方锐偷吃这一笔,这次的惩罚可能要让方锐捂着屁股走路了。 其实他没有写日记的习惯——参人也没有。一开始只是觉得这个经历很新奇需要记录下来,摄像是不被允许的写下来的东西更有感触。 也是这个记录的习惯让他被分到了监管的职责,他并不想但喻文州看出来了,大概是他表情过于用力拒绝了,对方不知道是不是从T市进修了立刻泫然欲泣来了段贯口:“变态的主人,乱跑的猫,修东西的老实人,破碎的我!新杰你忍心让我一个人管这一大家子吗。” 张新杰很想说忍心,但还是叹了口气:“好吧。”毕竟这人把全公馆能管事的都排除了一遍。 变态的主人:叶修,这个无名公馆的唯一主人,他们这群大男人穿着这袒胸露乳束腰女仆装的罪魁祸首。 乱跑的猫:王杰希,明明穿着靴子但是走路总是没有声音,疑似来这里享福度假经常在树上见到他,不知道怎么上去的。(后来张新杰看到此人从叶修书房的窗户爬出去) 修东西的老实人:肖时钦,大家各有各的本事但毕竟现在这个社会能锻炼动手能力的事太少了——打荣耀不算。一个公馆总得修修补补,肖时钦虽然说他真的不会但还是叹气上了。 破碎的他:喻文州,嗯,说好听点是公馆的二把手但底子就是白天上b班晚上b上班的苦命人,不过别担心我们有排班的不用日日b上班。 张新杰把这四个人记录在册,往前翻翻,翻到第一天进入这里时的见闻。 说了半天公馆,这里到底是什么地方呢?地理位置很奇怪在一个交叉之地谁都不管之处建立了这个公馆,都市传说的温床连环杀手在这里分尸都出来了,也亏的这个叶修才能低价入手。不过用张新杰的话讲这里是实现另一自我之地。 抛弃已经建立起的社会身份把自己交给另一个人。 角色扮演游戏,张新杰批注上。

夏休期,五湖四海天南海角大家齐聚一堂,没有人迟到按点进入会客厅,全是第一届世邀赛的熟人——圈子太小就是这样,各种意味的圈子。叶修抱着条狗坐在前面,狗叫小点,不过看起来挺老的,没玩一会就趴着睡了。 dom主和狗应该是很能体现暧昧与纪律氛围的场面,只是叶修和小点像出门逛街的对门、张新杰斟酌了一下用词写下了无业青年四个字。 现在无业青年给大家纷发手册合同,说这不是单纯的荣耀训练营啊现在退出还来得及哈,“签了名就跑不掉了。” 一时间大厅里只有翻纸的声音,一般人来看这些条款就像旧社会的卖身契,新时代的传销,半封建半殖民地时期的卖血长工,但对于他们这样的“圈内人士”来讲再平常不过了,有的人随便扫了两眼就要签了被叶修弹了额头:“仔细看看。”孙翔脑袋显然是刚补了发色,金灿灿的,捂着脑门把合同举着掩面看起来有点不好意思,旁边的唐昊也略微无语地看他——啊,唐昊。张新杰多写了两笔,这人来找过他,请求签订主仆关系,不过那时张新杰拒绝了连着呼啸的邀约一起。他看到我很惊讶,也是,毕竟我一直是dom位,但我并不是唯一的在这里做出转变的。 张新杰是看得很仔细那类,直到最后还就一些条款和叶修讨论,比如荣耀训练安排,比如“应在主人临睡时问候,我入睡时间比你早,这点需要再商讨。”至于“以温和克制的态度侍奉”张佳乐看到这条立马就提出来要保留个性了,叶修也同意了,两条都是,毕竟张新杰的入睡时间十分健康该改的是叶修才对吧! “希望我入睡时的问候能正好契合您的入睡时间,先生。”张新杰签下了自己的名字。 黄少天倒是对只能在主人允许时发言颇有微词但也只是嘀咕。如果他提出异议的话恐怕要变成限制字数了,张新杰写下这一句在这一页的末尾。 等合同全都收走后张佳乐先蹦出来说要看看叶修设计的衣服,“看看你审美怎么样!”合同写了在公馆要穿制服。 叶修颇为自豪地推出一个人台,他是得意了,其他人都沉默了——“这里就是空着的吗。”李轩问,指着人模傲人的塑料胸部。 “对啊。”叶修自顾自的开始讲解衣服的设计全然不顾所有人后退一步。 英式传统女仆装,黑长裙白围裙,假领口假袖口,“鞋子不太传统,给的是长靴但是你们可以穿自己喜欢的。” 我看最不传统的不是这个吧,张新杰写下所有人心里一定都在说这句话。 “这个腰带?还是什么……有点、有点……”孙翔一时间那个部位不知道叫什么,“束腰。”唐昊替他同期好兄弟说了:“有点太色情了。” 张新杰也这么觉得,这个皮质绑带束腰勒在比例极佳的模特身上都紧紧的,他们这群正常体格的大男人能呼吸得上来吗——旁边张佳乐倒是在掐着自己腰比划了嘀咕还能吗,被叶修拉过去说试试不就知道了。 张佳乐一激灵,捂着自己腰看起来像肚子疼:“在这啊?不行!”声音可能太大了,小点醒来见着张佳乐围着他绕圈。 “那你去后面?”他看着张佳乐蹲下来摸狗。 张新杰认为张佳乐对叶修是有感情在的——私底下见过很多次不然小点不会那么亲近他。所以张佳乐真的拆了束腰去后面了,就是有些恶狠狠的,还带着小点走了。 其实联盟的人大部分对叶修都有感情只是是正向的还是负面的就不好说了。 在张佳乐戴束腰的时间里黄少天在和喻文州耳语,叶修:“少天大大说什么呢,给我也听听。” “咳咳!就是那个那个模型上的那个乳钉是装饰还是也是制服标准啊,有些人没有乳钉吧现打?”黄少天这么一说大家才注意到那个所有人都下意识以为是增添情色氛围而有的装饰的东西。 叶修笑了下,有点坏:“哦,这个啊。”手放在人体模特的乳房上拨弄着,张新杰没有乳钉他看着有的那个几人不自觉地含了含肩膀。“这个不强求啊,只是这块的露肤度是有要求的。”他在乳房上比划出一片区域,“只能盖住那么多。” 张新杰写下,破窗效应,大家以为是全裸但他又退后一步,哪怕这块遮住的区域只符合最性感那种比基尼胸罩大小所有人也庆幸地接受了。 张佳乐和狗回来了,衣服宽松看不出什么变化,小点又趴在椅子下。 叶修:“过来我看看。”他掀起张佳乐的外衣让他自己拿着,张佳乐眼一瞪嘴一歪——还是拿着了。他掐着张佳乐的腰给大家展示:“看见没有还是能塞进去的啊。有点松,我给你重新绑一下。” 张新杰写张佳乐和叶修对视了几秒便转过去抱着叶修当支撑,背对着大家看不清表情只能看见这人肩胛骨都在用力叶修没被勒死也是铜墙铁壁了,叶修手下也黑,皮带扯到了最底扣上。 原来男人的腰也能这么细。 “看见没就这样啊。”叶修拍拍张佳乐屁股,张佳乐大概是缺氧了没有反击回去,回到队里的时候我撑着他。 “这是上刑吧!”众人沉默后方锐先暴鸣出来,连周泽楷都重重点头。 “他好久没戴了有些不习惯,等会就好了。你们可以松一点慢慢束紧啊。” “我擦你这束那么细,”黄少天比着张佳乐的腰,“胃都挤没了!怎么吃饭啊虐待啊!” “少食多餐吃多了晕碳,胃里东西少血液才能供大脑。” “看我干什么。”李轩挠头。 大家吐槽归吐槽其实接受度良好,又是一个破窗——可以慢慢束紧。腰还是裹得严严实实的胸口是实打实露出来了。 我决定穿比基尼,李轩找我商量我说了我的计划,他仰天长啸惆怅一会还是和我一起下单了。

片段

from REKISHI

开场就给叶修一个大怀抱,镜头对准了此人的胸部,能被叶修当成男人的胸那自然是乏善可陈的,他眯起眼睛看这白花花的胸口但没想到视频里的人手一捏竟然还有点料,在他的捏弄下肉嘟嘟的从指缝里挤出,没几下胸部便布满了红痕,乳头也挺立起来,这人乳晕比一般人要大但还是粉的,像个安慰奶嘴。随着火腿批发(真的要叫他这个名字吗?)的低喘他从镜头外拿出两个——叶修觉得是皮筋的东西,并且还不好用。两个看起来没什么弹性的粗皮筋下贴着粉色的毛茸球,但很明显出现在视频里不是用来扎头发的——叶修看着这粗皮筋就扎住了两边乳头,毛茸球正好贴在乳头下面像两个兔尾巴,十分可爱,火腿批发还掂了掂胸展示了一下,这两个毛茸球又各自坠了一条链子下去随着动作叮叮作响。

镜头向下顺着链子划过这人的小肚子到了大家都爱看的重点部位,叶修睁大眼睛暂停仔细看,画面停留在火腿批发两根手指别开大小阴唇展示着里面,整个屄白净,大阴唇鼓鼓的,如何合上的话大概会像个小馒头吧。他左看右看这个部位都很真不像p的,又敲了下空格进度条继续走,见此人沾了润滑在那条闭合的缝外来回抚摸最后摸起上面的凸起,凸起像个发芽扎根的豆子——让叶修来讲就是旺仔小馒头。他的手指在这点周围开始打着圈搔挠着那点,随着旺仔小馒头变旺仔小红豆挺立起来叶修和脑中的理论知识对上号了,这就是阴蒂。

此时阴蒂底下的那条缝也闪了条缝往外吐着液体,一动一动的,黏液挂在屄口,清液一滴一滴滚出来。那人新拿了个震动小玩具贴在阴蒂头边,从时不时的呻吟和一抖一抖的大腿来看是很爽的,画面一闪瞬间阴蒂充血颜色变深比整个屄高出一小节已然是玩熟的样子,切个了视角,好像叶修被这人屁股坐着脸鼻子就抵在屄上,镜头近的叶修幻嗅到一股味道。从下到上的视角可以看出阴蒂翘出了多高,阴蒂头充血肿起——这个画面给叶修的冲击还是有的,他都不知道这个部位可以伸这么长,并且那么像……几把?叶修如果有更丰富的生物知识的话会知道这两者的亲缘关系,就像他和叶秋一样。视角切回了正面,可以看出来火腿批发用力夹了一下屄,缓了缓从肚子上拣起那条快被遗忘的链子,这链子最底下有个小夹子,叶修瞬间知道了这个夹子的归属地,果不其然被人夹在了翘起的阴蒂上,夹上去那一刻水从屄里喷了出来弄模糊了镜头——然后就没了,后面是onlyfans专享。

叶修看着后面的onlyfans链接,又低头看看撑起来的裤裆——真是会吊人胃口啊!省略掉的过程大概是付费专属吧。这个视频叶修能给出很高评价:色调清新环境整洁,肉体也干净,该白的地方白该红的地方红,白的比如小肚子和整个屄,红的比如捏完的乳头玩过的阴蒂。干干净净没有毛,观赏性极佳,引人性欲方面也极佳。叶修踉踉跄跄溜去卫生间了,走之前还不忘清除历史记录。

卫生间里贤者时间的叶修头探出窗户点燃一根事后烟,冷风让他清醒不少,小头下去大头重新占领高地了:不对。大头思考了:我不是来看他打荣耀的吗,这也没打荣耀啊。

How they make the Social Network

from shu

#thesocialnetworkRPF, #thesocialnetwork, #jewnicorn

Chapter 1 [Boston]

Jesse承认,在波士顿开始摄制是个再好不过的主意。 这是个安静的城市,又因为大学的聚集而充满了年轻人——彼此矛盾的特质却在此处完美结合,总带给人即将要发生什么新鲜事的预感,一种充满可能性的静止。处于这座城市中很容易想象Facebook的诞生,酒吧里被甩、玻璃窗上的公式、溅起的啤酒和凌晨的键盘敲击声。 虽然后三件事严格意义上不在此地。H33内景在几个月后的摄影棚内,尚未被搭建。 剧组为他们订的酒店离片场不近不远,在不赶时间的时候,Jesse Eisenberg走路去片场。他在路上默词、进入角色、或只是体验这座城市,从他自己或Mark Zuckerberg的视角,或者介于两者之间。在早晨这么做总会遇到匆匆路过的本科生,和他们的书包、早餐三明治和黑眼圈。在Boston读书的本科生们总是很年轻,他联想到之前看到的扎克伯格大学时的相片,于是想象他和他们走在一起。一个帮助他自己更好进入工作的小游戏。

诚实地说,即使在会议室排演了三周,每一次实景拍摄依然令人兴奋——尤其当你的导演是David Fincher,一个致力于让一切场景显得真实的完美主义者。 此时他们正在一个酒吧的后门,拍那场全片的题眼。他在默诵台词时把social experience错念成social network,合理的错误,但需要注意不能真的发生。Andrew戴上那顶滑稽的帽子后更像Eduardo,虽然这么说有一点奇怪,但那顶帽子确实有一种巴西风情,也许是这个会放尼加拉瓜瀑布和诡异的彩虹光环的加勒比海派对里和加勒比海最有关系的东西。 拍这场时他们交换很多语句,在台前也在幕后。喊cut后他们心照不宣地留在角色的状态里继续谈话,那感觉很好,他是说,那一个晚上里他和Andrew拉近的距离比三周排演的总和还要多,给之后的场景帮了大忙。 杂物间里除了他们还有剧组人员,拍摄纪录片的摄像头对着他们,但这一切在这一刻都无关紧要。他们随意地讲话,评价对方的表演,也说一些突然蹦到脑子里的毫无意义的蠢话,并在对上电波时朝着彼此大笑,像一对真正的大学好友。 或许这就是关系的本质,谁知道呢?

from suberr

透明心事

cp:布茸 转生。布茸米有记忆,其余无,全员无替身。 布加拉提失明。

“你在干什么?”布加拉提问道。 我在看你的眼睛。倘若乔鲁诺这么回答,布加拉提一定会露出有点困惑又束手无策的表情,绞尽脑汁思考怎么安慰他吧。但乔鲁诺不希望布加拉提反过来顾虑自己的心情,“我带了一本游记来看。” 这句话只有一半是真的。那本书一直待在包里,乔鲁诺就没拿出来翻过。不知道布加拉提有没有注意到,对方只是笑了笑,没再说话,重新开始手上的工作。 就算乔鲁诺把他盯穿了他也发现不了。因为那双蓝瞳已经蒙上一层灰,像是教堂镶窗的磨砂蓝玻璃似的,失去了记忆中的神采。 这一世的布加拉提看不见。

乔鲁诺本打算一切都安顿好了再去找布加拉提的。 前世并肩作战的记忆支撑他度过了黑暗的童年时期。这个世界不存在替身能力,夺取热情组织花了他好一番功夫;但也多亏如此,迪亚波罗的防守也没那么密不透风了,最先加入的米斯达也帮了他很多。后来他俩又找到了福葛、纳兰迦、阿帕基和特莉休。其余人等似乎都没有前世的记忆。所以他和米斯达常常两个人在一起聊天,最后话题总会落到布加拉提的去向上。当乔鲁诺变得消沉时,米斯达总是乐观地鼓励他一定能找到的。 某日米斯达兴奋地冲进boss室说,“找到了!”乔鲁诺闻言也兴奋地从座椅上弹起来。但米斯达随即又吞吞吐吐起来,“……找是找到了,你听了不要太震惊。” 据米斯达说他是饿得要死的时候,随便走进街边的一家面包店,意外发现布加拉提就是那里的店长。布加拉提也记得他,还高兴地请他饱餐了一顿。 乔鲁诺想,组织不是在收保护费,会有人就在眼皮底下一直没发现这么荒诞的事?但是毕竟是最末端的小喽啰去收的,也有可能啊…… “所以,那个店在哪里?” 米斯达一说地址,乔鲁诺立刻跑了出去,没听米斯达把话说完。

布加拉提靠声音认出了乔鲁诺。他安排乔鲁诺在店里的小桌子边坐下,熟练地摸索着给他倒了一杯咖啡。 布加拉提说,“我从小就看不见,视野中只有模糊的光亮,是先天的,已经习惯了,也没什么不方便的。” “啊,但是不能打渔是有点不方便。你看,万一掉进海里,也不知道船在哪个方向,该往哪里游吧,”布加拉提又笑笑,“所以我离开家学做面包了。” 接着布加拉提告诉他可以靠手感来确认面团的发酵程度、称粉时天秤可以语音报重量、烤箱可以用旋钮的,总之“日子还过得下去”。 乔鲁诺没听进去,他只是把右手放在布加拉提的眼眶处。似乎感觉到视野变暗了,布加拉提疑惑地喊了一声“乔鲁诺?”乔鲁诺没回应,默默呼唤黄金体验。 空气中什么都没出现。他不能再给布加拉提创造一对完好的眼睛了。 乔鲁诺收回了手。

乔鲁诺花了一点时间才接受了现实。之后他开始经常往布加拉提的面包店跑。他带着作业去面包店做,做完以后就坐在那里看布加拉提做面包,像一切等男友下班的女高中生似的。布加拉提不可能知道乔鲁诺在干什么,也算这种情况下难得的心理安慰。一来二去连布加拉提雇用的两个店员都眼熟他了,乔鲁诺虽然有点不好意思,但又理直气壮地用“是朋友”来掩饰。 这天乔鲁诺要处理一桩组织成员内斗的事,赶到面包店的时候天已经黑了。只见店里一片狼藉,布加拉提正用扫帚扫着被打破的玻璃碎片。 “发生什么事了?” 听到是乔鲁诺的声音,布加拉提抬起头来,空洞的眼睛对着他,云淡风轻地说,“没什么大事。刚才有两个男孩来抢劫,拿刀威胁了艾莉,她受惊了,我就让她先回去了。不过现在大家都是用卡付款的多,收银机也只有十几欧,损失不大,总觉得让他们白跑一趟了呵呵。” “为什么不打电话给我?打给米斯达也行吧,给阿帕基也行吧!我们一定会赶来的!” 布加拉提沉默片刻,认真地说,“我不想因为眼睛看不见了,就什么事都依靠你们。这种小事,我会处理好。” 乔鲁诺生气地揪住布加拉提的衣服,“这可不是‘小事’!你明白吗?我已经没有黄金体验了,万一真的发生什么就晚了,我无法救你了……布加拉提……” 乔鲁诺说着,气势渐渐弱了下去,最后倚靠在对方身上。布加拉提叹了口气,摸了摸他的头,“抱歉,乔鲁诺,明明不想让你担心的,好像还是害你伤心了。原谅我吧。” 乔鲁诺依旧抵着他的胸膛不说话,于是布加拉提丢开了扫帚,抱住了乔鲁诺。 尽管布加拉提说那两个男孩像是生活遇到了什么困难,叮嘱乔鲁诺网开一面、不用找他们麻烦。乔鲁诺还是派人抓回来,压在组织做义工,以抵销面包店的维修费。接着,不知为什么城里流传出一条小道消息,说这家面包店是热情boss罩着的,敢惹事的人都下场惨烈。从此布加拉提的小生意便平稳无波了。

米斯达跟乔鲁诺倾述的三番五次追求特莉休无果的恋爱话题,乔鲁诺总是左耳进右耳出。但他今天却神秘兮兮地对乔鲁诺说,“前些天啊,我看见布加拉提和那个女店员捧着花走在一起哦,好像叫艾莉是吧。你说他们会不会在谈恋爱啊?” 乔鲁诺表情一冷,“不可能,布加拉提会告诉我们的。” “你想想啊,这辈子那女人比你我遇见布加拉提都早吧,说不定早就有一腿了,布加拉提是想等订婚的时候再宣布呢。” 想到那晚布加拉提说到艾莉的样子,乔鲁诺猛地站起来。他虽然年轻,但生起气来很有黑手党boss的威严,被他一瞪,米斯达也不敢再说下去了。乔鲁诺丢下一句“我要去买巧克力”就离开了。 那只是个借口。巧克力无论是办公室还是布加拉提的面包店都囤有一堆。乔鲁诺在街上漫步,不知不觉又朝着面包店走去。于是他正好看见布加拉提和艾莉有说有笑地从另一个方向走来,当然手上还捧着花,俊男美女,怎么看都像在约会。 艾莉先发现了他,朝他打了个招呼。布加拉提这才“注意”到了乔鲁诺,视线转向了他。艾莉辞别了两人,抱着花快步走向面包店。现场只剩下乔鲁诺和布加拉提两人。 布加拉提不可思议地问,“怎么了,乔鲁诺,好像你心情不太好,艾莉有点害怕。” 又是艾莉。“你就这样丢下生意不做了吗?” “今天轮班,是丹在看店。”来者不善,布加拉提也呛了回去,“我可不记得有收过你的注资哦,乔鲁诺。” “……是约会吗。” “不是,只是去买店里装饰用的鲜花而已。我看不见,还是和她一起去比较方便。” “什么啊,原来是这样。”乔鲁诺松了一口气,表情也明亮起来。他小声嘀咕那就别让人误会啊。 “要买花的话,下次我跟你去,”乔鲁诺说,“因为我没有替身了,不能给你变出花来。所以我跟你去。” 这是什么道理啊。不过乔鲁诺听起来心情好多了,就随便他吧。布加拉提想。他提了另一个疑惑不解的问题,“总觉得你情绪波动很大……我记得前世无论遇到什么险境,你都能冷静应对,是我的错觉吗?” “我是……失去过你一次以后,就变得有点患得患失了。”虽然布加拉提看不见,乔鲁诺仍不由得别过脸。他觉得现在脸烫得跟火山喷发一样,布加拉提看不见真是太好了,不,不好。 “不想失去我?” “嗯。” “这是告白?”布加拉提又补充了一句,“啊,我是开玩笑的。” “如果真的是告白呢,如果我说我喜欢你呢,布加拉提?” “我看不见。” “嗯。” “我没有替身。” “我也没有。” “我会拖累你这个黑帮老大的。”布加拉提笑了。 “我又没有弱小到会被你拖累!” 布加拉提伸出手找乔鲁诺,但在空气中扑了个空。乔鲁诺主动抓住了他。布加拉提握住那只手吻了一下,开口说道,“我啊,虽然看不见,生活是有点不便,但一直没有什么不满,那些困难总能克服下来。但是我第一次觉得很可惜,看不到你慢慢变老的样子了。我的脑海里永远是那个15岁的你了。” “这是?” “这是求婚哦,乔鲁诺。” “我很高兴,”乔鲁诺露出了金色的笑容,“我就永远当你心中15岁的乔鲁诺吧。”

Fin

from suberr

段子

cp:布茸 转生。登场角色均满合法饮酒年龄。

福葛问某酒吧正好进了一批荔枝,要不要去尝尝。 是时乔鲁诺正和福葛两人在米兰出差,米斯达守着那不勒斯的大本营。福葛所说的酒吧就位于米兰的唐人街里。 乔鲁诺并非不胜酒力,却也没有特别喜欢喝酒。何况身为组织的boss,他并不缺人送酒,部下和合作伙伴借口各种节庆送来的酒已经塞满了热情的地窖。因此他有点好奇福葛为什么会邀请自己。 福葛歪着头答,心血来潮? 乔鲁诺也同样心血来潮地答应了福葛的邀约。

乔鲁诺是带着前世的记忆转生的,于是他就像带着通关攻略一样早早觉醒了替身,打爆了家暴的继父和找碴的小屁孩,潜伏进热情并夺取了帝位。他注定是要当上黑帮明星的。站上权力之巅后,他感到有些无聊,开始寻找前世的伙伴们。 乔鲁诺最先找到的是福葛,他没来得及阻止大学里发生的一切,无处可去的福葛就这样成为了他的有力干将;但经过乔鲁诺亲力亲为的一番整顿,街上的治安变好了,阿帕基继续当他的人民公仆,纳兰迦也被福葛督促着读书(并留级),米斯达以“今天去钓鱼吧”这种不以为然的心态入了伙。不久他又看到特莉休签约歌手出道的新闻,他以热情的名义给那家经纪公司投了笔钱,嘱托董事多多“关照”这位明日之星。 所有人都没有前世的记忆,大家只觉得乔鲁诺很亲切,很好说话,体贴入微到没等他们说出口就包容了他们的怪癖,有点神乎其技了。但是,15岁就当上了热情的boss,还有什么是无敌的JOJO做不到的呢?连福葛都放弃了思考。 然而乔鲁诺却怎么也找不到最想念的布加拉提。布加拉提就像清晨的露水一样从他的世界蒸发了。 福葛也曾提议下发通缉令捉拿这个“欠了乔鲁诺6亿欧的坏蛋”,乔鲁诺又阻止说不用了。乔鲁诺说只是朋友,不用这么大张旗鼓。福葛第一次觉得自己的boss反复无常。

酒吧位于地下一层,拥有酒吧特有的湿润沉闷的空气。乔鲁诺几乎刚进门就后悔了,但他还是说话算话,任由福葛将自己带到靠近换气口的吧台一端。吧台的荧光板上用英意语和汉字写着“季节限定 荔枝马丁尼”。就是这个吗,乔鲁诺用眼神询问。福葛点了点头。 福葛朝吧台里面喊,“晚上好,我们要两杯荔枝马丁尼。” 闻言,本来蹲着的酒保便端着一个小泡沫箱站了起来。这可不就是布加拉提。 他先朝福葛打招呼,“呀,福葛,好久不见。”又问福葛带来的同伴是谁。 乔鲁诺抢在福葛之前开口道,“我是乔鲁诺•乔巴拿,是福葛的上司。” 布加拉提的表情并未改变,仍是笑意盈盈接客的样子,“你好啊,乔鲁诺,很高兴认识你。”

一无所知的布加拉提从放着冰块的泡沫箱里拿出“早上才空运到的新鲜荔枝”,手指划开一条小拉链,荔枝凹凸不平的红色外壳随即裂成两半,露出雪白的球体。他又故伎重施,得到了剥离果核而无损失的完整果肉。直到布加拉提剥完8颗荔枝,台面都干干净净,没滴下一滴汁水。 乔鲁诺想,用钢链手指做这种事,真是大材小用。 但布加拉提本人却似乎乐在其中。所以乔鲁诺什么也没说。 他曾经无数次想过,布加拉提的替身是为了黑帮而生的,但布加拉提却不适合当黑帮,他在别处才能得到真正的安宁。 布加拉提将过滤好的酒液分进两个马丁尼杯,推到乔鲁诺和福葛面前。乔鲁诺一饮而尽,微苦液体流下喉管的同时,清新的荔枝香气扩散到整个大脑。 乔鲁诺递回空杯,“再来一杯!” 福葛大惊失色,“乔鲁诺,基酒可是45°的伏特加啊!” “福葛,你知道我不怕醉的。”乔鲁诺说道,眼神却钉在布加拉提身上。 布加拉提剥起了荔枝,很快又做好了一杯马丁尼,不过几秒又消失在乔鲁诺的喉咙里。 再来一杯。再来一杯。再来一杯。 乔鲁诺没数自己到底喝了多少杯,只是长久地注视布加拉提,似乎要把这一切烙印在视网膜上。 最后布加拉提也忍不住苦笑说,“我这一晚真是被困在这里了”、“一批次的荔枝一晚上就要被乔鲁诺吃完了虽然我是很感激”。他还关心乔鲁诺喝太多酒会不会胃不舒服。 乔鲁诺冷不防问道,“布加拉提,你现在幸福吗?” 布加拉提虽然冒出了个“?”,但也温柔地回答,“我很幸福,也很满足。” “是吗。”乔鲁诺喝掉了最后一杯荔枝马丁尼。

乔鲁诺被福葛搀着走出了打烊的酒吧。到了没人的地方,聪敏的福葛这才吐露了纠结整晚的疑问,“乔鲁诺,他就是你要找的人吗?” 乔鲁诺说道,“不,他不是。” 荔枝的香气,似乎要消散掉了。

完

from GrandDBlood1

[Lancer双枪]公主抱挑战 cp:迪卢木多/库丘林 无差 闪恩提及 搞笑向 ooc有 闪恩史诗梗提及 对游戏设定不太了解但使用 因故彻夜上头的作者在翻粮的过程中看到了作者会在意的角色设定,写了作者擅长的题材。(其实用到短视频热梗,注意避雷)

迦勒底健身房(一般是御主和研究人员在用,有时也有英灵消遣和练习),迪卢木多、库丘林、吉尔伽美什三人,在下午茶刚过的时段聚在这里,健身房里没有其他人。 吉尔伽美什:“不是,公主抱挑战为什么要叫我来,蓝色的狗,你想做什么?”金色的王其实有些无奈,但先答允了光之子提议的迪卢木多很诚恳地帮腔邀请他,他便来了。王,意外地好说话呢。 库丘林有自己的小心思,迪卢木多也有自己的好奇,只是这些思考,似乎需要一个局外人,将其变成平常的事情。

“嘿,这不是需要成日穿着黄金铠甲的强大英灵的指导嘛!”枪兵有些没正形地露出了牙齿。

“哦~”,英雄王抱臂胸前,“要赌些什么吗?”

迪卢木多真诚地疑惑着,“其实筋力这些东西,查阅档案即可满足好奇心吧?说到底我并不明白这个挑战的必要性,也不知道能赌些什么?”疑惑到手指摩挲着下巴。 对!就是档案!光之子自从在迦和“光辉之貌”的后辈搭上线,虽不会被泪痣魅惑,对迪卢木多美型的身材也是颇多关注,某天翻看档案(只是闲的),竟发现迪卢木多体重是85kg,这让只有70kg超模体重的半人半神颇为震惊(迪卢:你这个体重还有这么大肌肉才应该奇怪好吧?!),不知是否出于想揩油,大抵是有好奇,于是发起了三人的公主抱挑战。

“赌谁被抱起来表情变化最大,输了的穿瑜伽裤跳*站经典健身操。”旋转突进的蓝色枪兵也抱着臂,手指一弹,亮了个灯泡。 好家伙,原来是耻感挑战吗!那么筋力不相上下的人确实有挑战的意义了。似是摸清大狗提议意图的二人接下了挑战。(王,是否有些ooc了,迪卢酱有天然属性也就罢了) 黄金王打开了王财,拿出了不知何人赠予的昂贵相机和支架(广告位招租),说:“好,视频为证,之后用计算机分析。”王是否在现世沾染了一些IT理工男气息,抑或是某种战力阿宅。 两位枪兵不禁扶额。 大狗不知从何处掏出狗耳发箍戴到了头上,说:“既然认真起来了,服饰也可以作为挑战的道具喽!”在燃个什么劲啊。 枪刷扑哧一笑,光之子戴这个真是合适啊!

“哦~”,英雄王眉毛一挑,“那我直接随机加强铠甲的重量也可以啊。”喂,王,是要被抱的人表情变化,不是抱的人举不起来脸部代偿。

“哦!那我可以要求使用魅惑魔术!”迪卢十分正义的闪光表情。 虽然另两位性向也很灵活啦,但是你确定他们会产生耻感,迪卢酱?

一番互相挑衅后,三人正式打开了相机。

“那么,我先来抱吧!”汪酱甚至穿了会不时摇动的尾巴装饰。 迪卢木多十分绅士地请吉尔先,吉尔向伸开双手面向健身房整面墙镜子的库丘林走去,全身的铠甲一如既往发出“吭啷吭啷”的清脆声响。 英雄王是一个很没有耻感的人,平日狂妄的表情就那么几种,到过劳死都面部舒展没留下什么皱纹,可谓笑一笑十年少,他很有确信能赢。(再说了,就算穿瑜伽裤王也会欣赏自己的翘臀吧,只是款式得时尚,作者小小声os……)再说,威严,权力,一张脸放在那里,细微的表情和强大的气场,吉尔伽美什擅长传达这个,本身就是王中之王。 库丘林则在掂量,好,这是68kg加上铠甲重量未知。 吉尔一手搭在库兰的萌犬颈后,似是有些被逗笑了,镜中的自己挺拔,而镜中的狗很明显在思考别的事情,耳朵和尾巴却在电力提供下不时展露存在感,但王只是微微一笑。 毕竟世间众多萌物或是反差,王也是尽览。

“接下来是我喽,御子殿下。”迪卢木多微笑着说。

萌犬心中不察地一颤。是在思考那15kg都长在哪儿了吗? 两人身高只相差了1cm,体型也不能说是差距很大,迪卢木多走近前来,库丘林双腿微蹲,尾巴不时扫动,而表情却很认真。迪卢木多困惑着,但他眉毛本就微蹙,深邃的双眼看不出多大变化来。两人因姿势并没有对上视线。 然而抱起来看向镜子的刹那,库丘林震惊于85kg的手感,表情傻傻地凝固,迪卢木多则由于库丘林震惊而手指摸在**位置而脸颊爆红,蒸出热气。金色的王在旁哈哈大笑。

“傻狗,等下我帮迪卢告你性骚扰了。”王一边捧腹,画风变成嘉年华边说着。

下来之后,迪卢掩面说着:“等下这个能不作数吗?”

王眼泪都笑出来,拍着他的肩说道:“耻感挑战,很明显规则空间包括这种,青年人,梦是要醒的。”迪卢掩面。

下一个是吉尔来抱,光之子先,有一位要先缓下情绪。 吉尔伽美什抱起身形大过自己的大狗,讲了一个人类最古冷笑话,大狗瀑布汗。耻感挑战变笑点挑战。 “汗”的表情已经有点幅度了,吉尔将大狗掂了两下,库丘林短暂地滞空了,手还虚扶着吉尔的颈后,听到吉尔说,“你知道吗?昨天Master用一只鞋子钓到了鱼妈妈和一串鱼孩子。” 大狗破防。

好…好强!迪卢木多在一旁暗暗感叹,在走过去被抱前暗自把破防史(实际是人生史)过了一遍,放弃了,一定程度。 吉尔双手抱起85kg的迪卢木多,或许还有几kg的衣甲,并没有讲什么逗乐的话,他看着镜中迪卢俊美眼下的泪痣,说道:“你可愿意成为我的臣下?”

迪卢怎么能不瞪大了眼睛呢。吉尔又说道:“我有这样的器量,可以容许你的存在,回应你的效忠。”真诚得听起来不像一贯在威慑的人。迪卢静静地听着。

“而且我老婆是专门为我定制的,平时经常躺在王财里睡大觉,只会抽冷子辅助我给对手致命一击,没空看帅哥啊~”尾音十分贱贱。迪卢完全撇嘴翻白眼,大狗则为吉尔的致命一击晕倒。实际上王和那位挚友不管从习性到经历到外貌,是 史诗级 的王八看绿豆啊。吉尔只是在练习跟某些圣杯守护者学的综艺主持技能。 看来胜者绝对有吉尔伽美什一个了。

接下来是迪卢木多来抱,作为三人中唯一的筋力B+,抱两位超模体重的英灵实在不在话下。 先是大狗来,因为另一位让迪卢木多拳头和五把刷子有点痒。

迪卢木多此前看着光之子也常常在想,是因为半人半神吗,光之子总有超越一些界限的力量,但身材只是普遍范围,这个闪着光的,时而开朗时而狰狞的,擅长卢恩魔术的,幸运E的(喂!)……前辈,如何做到这一切呢?靠的是眼前没有这些干扰吗。他来到迦勒底后会思考一些这样的问题。 他抱起这个身上有水火气息的人(什么?钓鱼和蹭卫宫家的饭吗),双眼看进他眼里,想要得到一些答案。

迪卢木多的黄色眼瞳此刻对他有些太刺眼了,库丘林眯缝起双眼,扭头看向镜子,发现自己的“尾巴”还在摇,而一旁的黄金王似乎在一手在手机码字,一手用王财打电话,说着些什么“小恩我跟你说我有个瓜……”电话那头传来同样爽朗的笑声…… 登时库丘林的脸穿刺死棘之枪的气势都要拿出来了。 尾巴不时扫在俊美85kg后辈的身上。 其实是破防挑战吧…… 库丘林已经想下来在一旁煮一锅蛇肉来吃了,看看某位会不会流口水。不过他没有那么做。

这时破门而入的(为什么要破门)红a看着这个场景低低笑出声,“喂,你们三个傻子在这里玩儿什么呢?”

三人齐齐转头,“啊?”

红a收敛了笑声,“哦,没什么,我只是来叫你们吃饭,今天做了全鱼宴,怕御主被鱼刺卡喉变成吃蘑菇后看见的小人,特来请各位多吃点。” 黄金的吉尔也敛了笑,说道,“那就到这里吧,反正输家肯定是狗,剩下的也没必要了。狗,记得挑下瑜伽裤,我这里相机随时支持。”说罢去往红a消失的方向。

库丘林挠挠脸,红a刚说完一句他俩就分开了,此时他没再看向迪卢木多的脸。他有点松了口气,对于吉尔说“剩下的算了”,因为他有点不想看见迪卢抱他。才不是因为他没再提一遍全鱼宴的鱼怎么来的呢!

迪卢木多站着,看着他屁股上方的尾巴,没来由地有些不好意思,于是他走上前,说:“御子殿下,去吃饭吗?”

“哦!”库丘林应声,走了两步,说:“过两天天气好,要和我一起去钓鱼吗?”只是说,并没有回头。

迪卢木多忍不住又看向那个固定频率摇动的尾巴,回答道:“好啊。不空军的话我们可以直接在岸边做来吃。”

“嘁!”库丘林大跨步往前走。

迪卢木多追了两步,跟着他。“前辈!把那尾巴摘了吧!”